When you take an English immersion course, you have a great opportunity to expand your vocabulary in English. But how do you make the new words stick in your long-term memory, so that you remember them not just tomorrow, but next week, next month, next year?

Here are 5 tips for making new words part of your permanent English vocabulary:

Be hungry for new words

Learn actively, rather than passively. Learning vocabulary from a list is boring and ineffective. Instead, when someone uses a word in conversation that is new for you, ask her/him to explain it to you. Repeat it aloud a few times and ask for feedback on your pronunciation. Ask how to spell it and write it down in a notebook. When you see a new word in your reading, copy it in your notebook, along with a short definition and the context in which you found the word.

Keep to the target language

to the target language

Translating the new word into your native language might help you get a quick understanding of a new word, at least in a general sense, but it actually makes it more difficult to remember the meaning of the new word the next time you hear it or see it, which after all is the main point.

Also, most words, individually and out of context, cannot accurately be translated – change the context, and you often have to change the translation. Abstract words are particularly and notoriously difficult to translate.

Explore the word from many angles

Learning a new word might start with the answer to the question What does it mean?. But there are also the questions How do you pronounce it?, How do you spell it?, and crucially if you really want to make the word your own, How do you use it with other words?

For example, if you use a noun after the verb depend, you have to use the preposition on, as in it depends on the weather (not depends of – an understandably common mistake for Spanish speakers translating word for word from Spanish to English).

Other ways of looking at a new word that can help you not only use it correctly but make it more memorable include:

Tone – is it formal or informal, pejorative or neutral, current slang or old-fashioned, etc? There is a world of difference, for example, between the synonyms smell, scent, stink, stench, odor, and perfume.

Word families and word history – the word trust, for example, comes from an Old Norse (Scandinavian) word for strong, can be used as both a verb and a noun, and is part of the same family of words as the adjectives trusting (trusting others), trustworthy (deserving of trust by others), and trusty (reliable and faithful for a long time).

Familiarity – learn the most common way to say something first. If you want to talk about a lot of precipitation in a short amount of time, first learn: It’s raining hard. Then: It’s pouring. Attempts to impress people with fancy-sounding idioms often backfire (bring about the opposite result), as with the cloying cliché It’s raining cats and dogs.

Google word definitions feature a graph that shows the popularity of a word over time: trusty, for example, was more popular in 1800 than it is now, while spin has skyrocketed in popularity since 1950, maybe because of its frequent use in modern political talk to mean a biased interpretation intended to influence public opinion.

Give the word a rich context

Memory works best by association. If the first time you encounter the word upshot (eventual outcome or result) is in an alphabetical list of words with prepositions as prefixes (upbeat, upend, upshot, uptake, upturn), chances are that all of those up-words will blend together and you won’t remember which is which.

If, instead, the first time you hear upshot is in a story with many twists and turns that ends with the tagline and the upshot was I got the job, or and the upshot was that there was enough lobster for everyone, the entire context of the story, even the room you were in when you heard the story and the expression of the storyteller when he reached the story’s end – all of these atmospheric details contribute towards making the new word memorable.

If, instead, the first time you hear upshot is in a story with many twists and turns that ends with the tagline and the upshot was I got the job, or and the upshot was that there was enough lobster for everyone, the entire context of the story, even the room you were in when you heard the story and the expression of the storyteller when he reached the story’s end – all of these atmospheric details contribute towards making the new word memorable.

For memorability, nothing can rival seeing and experiencing a word in the real world. That’s why excursions during an immersion course are such a great way to learn new vocabulary. Picking wild blueberries is by far the best way to learn the difference between the verb pick and the phrasal verb pick up.

Practice the word

To make a new word not just memorable but unforgettable, you have to start using it, in conversation and in writing, and the sooner and the oftener the better. According to James Gupta, a medical researcher at Leeds University, “We know that the brain preferentially stores information it deems to be important. It strengthens and consolidates memories of things it encounters regularly and frequently. So spaced repetition –revisiting information regularly at set intervals over time – makes a lot of sense.”

Keep a list of the words you are trying to learn, and return frequently to them, especially the ones that seem hardest to remember. Repetition is the key. Ask native speakers for more examples of how to use a new word in context. Try using it yourself, and make adjustments in how you use the word based on feedback from native speakers.

Be on the lookout for new words. Avoid translation. Investigate the word. Make it memorable through context. Practice and put it to use right away. And the upshot will be that you will have added many new words to your vocabulary.

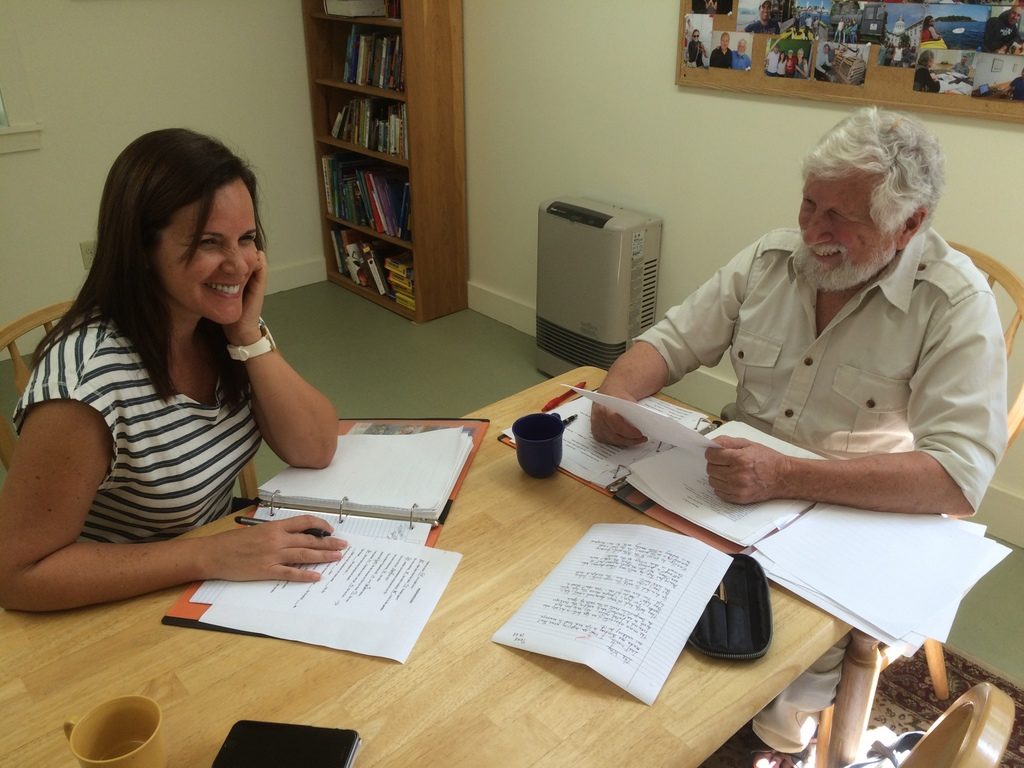

You’ve heard of eco-tourism. What about talking-tourism or conversation-tourism?

You’ve heard of eco-tourism. What about talking-tourism or conversation-tourism? Nature and conservation is the passion of another student of ours, an executive from Barcelona, and the excursions designed for him included a tour of a woodland management project with a local forester and otter and owl tracking in a nearby nature preserve with a local ecologist and wildlife expert.

Nature and conservation is the passion of another student of ours, an executive from Barcelona, and the excursions designed for him included a tour of a woodland management project with a local forester and otter and owl tracking in a nearby nature preserve with a local ecologist and wildlife expert. to the target language

to the target language